Favorites: The Crisis of European Culture. External story structure

Who, under his leadership, defended his doctoral dissertation. Weber's essay had a great influence on Kafka's artistic work. "Official" (1910).

During the Prague period of creativity, modifying Heinrich Thunen’s model of the location of zones of different agricultural activities for industrial production, Weber built a theory of industrial location. According to this theory, an industrial enterprise strives to occupy the most advantageous position in relation to sources of raw materials and the labor market, providing the lowest costs for entrepreneurs. Weber's theory became part of economic geography and brought him international fame. Weber planned to release the second part of his work on this topic, but it never saw the light of day.

During this period, under the direct influence of M. Weber and the ideas of representatives of the philosophy of life (Nietzsche, Bergson, Spengler, Dilthey, Simmel), Weber's interests moved to the field of sociology. Like Spengler, Weber is trying to create a science of the “historical world” that allows his contemporaries to orient themselves regarding their present and future. But, unlike Spengler, he proceeds from the conviction that it should not be philosophy, but the sociology of history. In the early 1920s, Weber formulated a program for creating a sociology of history and culture and over the next almost forty years he implemented it in his numerous works. In fact, the sociology of history and culture has become a kind of synthesis of philosophy of life, national economic analysis, cultural history and politics.

Political activity

Weber was not an armchair scientist and always sought to implement his ideas in practical political activity. “We want to act,” he said during one of his speeches. In his reports, articles and oral presentations, Weber called for social and democratic reforms, the humanization of the workers' world, and a stronger role for parliament in the political system.

Having devoted his life to science, teaching and practical politics, Weber never created his own family. Having not founded a scientific school in the strict sense of the word, he nevertheless had a profound influence on his numerous students, among whom were different years there were Karl Mannheim, Norbert Elias, Erich Fromm and others.

Alfred Weber as an economist

In 1909, Weber's work “The Pure Theory of Industrial Location” was published, which was a development of the standart theories of industrial location by Johann von Thunen and Wilhelm Launhardt. Considering the placement of a single enterprise in relation to the main factors of production in order to minimize costs, Weber introduces the concept isodapane- lines of equal costs of deviation from the optimal position of the enterprise. Weber considered labor, the cost of raw materials and fuel resources, and transportation costs for moving them to each other as factors influencing the location. Weber's model remained central to the theory of industrial location until the mid-1930s, when it was criticized by August Lösch and a number of American economists and geographers.

Subject and method of cultural sociological knowledge

Sphere social process represents a kind of sociological reconstruction of the historical process. It is formed by the sociologist himself when he “groups into a new, adequate form of representation, given to him by a historian, the concretely individualized material of the “material” development of various historical spheres.” Social process is the sphere of economy, social relations, politics and the state in which aspirations are expressed and human volitional powers. Economic factors here are not separated from geographical and biological ones.

The social process of historical bodies goes through various stages, following from simple to more complex forms of “vital synthesis”. In the course of this development, he “undergoes complete regroupings of society, expansion and narrowing of his horizon, ossification and disintegration social forms" And although the development process taking place within each “historical body” is individual in nature, at the same time, some common features can be found in it. Thus, first, primitive initial forms appear, then they are replaced by more developed “generic” forms, and, finally, typical final forms appear.

Sociologists and social thinkers are accustomed to seeing two vast areas in the historical body: on the one hand, the area of the material social process based primarily “on natural inclinations and wills,” and on the other, the spiritual and cultural sphere. However, a closer examination reveals that within the spiritual-cultural sphere itself there is also a so-called “spiritual-intermediate area”, which is “in a much closer and clearly cognizable connection” with the image and course of the social process than cultural phenomena, the emergence of religion, systems of ideas, periods of art, etc. The spiritual and cultural sphere, traditionally understood as something unified, actually includes two fundamentally different spheres of historical development.

The second sphere of the historical process is process of civilization. All large historical bodies (Chinese, Indian, ancient, Western, etc.) are characterized by a steady development of consciousness, obeying practically the same law. Consciousness develops from primitive stages, close to today's primitive and semi-cultural peoples, through overcoming totemic and then mythical ideas to an increasingly greater reflection of existence and the construction of a rationalized system of understanding the world. At the same time, not only a person’s external experiences, but also his own - emotions, drives and intellectual ideas - undergo intellectual “elaboration”. The development of individual consciousness leads, in turn, at the social level to the intellectual formation of “a practically useful scientific cosmos, experience and knowledge of life,” which, when materialized and concretized, is transformed from a practical system of knowledge into something completely real.

The process of rationalization, which has its own laws of development and conditions of stagnation, inevitably and steadily passes through all historical bodies. This process is something completely different from the process of the emergence of religions, systems of ideas, works of art and cultures. The process of intellectualization and rationalization consists of three parts: 1) “internal intellectual illumination” (that is, the formation of an intellectually formed image of the world and), 2) “intellectual formation of knowledge” (that is, the cosmos of practically intellectual knowledge) and 3) “intellectualized external mediating apparatus "(that is, the cosmos of an intellectually formed mediating apparatus of domination over existence). Despite the fact that in different historical bodies the process of civilization can reach different levels and give the image of the world it creates significantly different forms of expression, nevertheless, step by step it builds a cosmos of knowledge in each historical body. Its formation, set in motion in one direction, proceeds logically and naturally further, just as the construction of a building is subject to the laws of a certain immanent causality.

Everything that is revealed in the process of development of civilization is always not “created”, but “discovered”, that is, in a certain sense, it pre-exists and, as this cosmos of knowledge develops, it is only drawn into the sphere of conscious human existence. The above applies both to knowledge in its theoretical and practical aspects, and to the technical apparatus of existence. “The laws of Euclidean geometry “existed” before they were discovered, otherwise they could not have been discovered; also the Copernican formulas of the movement of the world, and Kant’s a priori, since they are all “correctly” discovered and formulated. Exactly the same - the steam engine, telephone, telegraph, axe, shovel, paper money and in general all available means, methods and principles of domination over nature and existence; all of these are “objects” of the practically intellectual cosmos of our existence; everything that we already possess, and everything that we will yet acquire, exists in its essence, “pre-exists” before we manage to introduce it into the conscious sphere of our existence and make it serve us.”

Due to their general significance and universality, the objects of the world of civilization, as soon as they are discovered in any historical body and introduced into conscious existence, spread throughout the world through wave movement and find application in all other historical bodies and, thus, become a universal property ( naturally, provided that the social process in these bodies has already reached a sufficiently high level, and the mental enlightenment of consciousness is so developed that it is able to “see” them).

Based on the fact that the phenomenology of the implementation and development of the cosmos of civilization is, in principle, the same for various historical bodies, V. concludes that in the development of their civilization they are completely correlated with each other and, as if, according to an established plan, they are working to identify something single.

“With this consideration, the entire historical process in all its parts is, strictly speaking, only a process of a single revelation of the cosmos of the civilization of mankind, which occurs with peculiar breaks, stages and faults associated with the fate of various historical bodies. The ancient Near Asian-Egyptian, ancient, Arabic, today's Western European historical sphere and the Chinese and Indian, which are in a weaker connection with them - all of them, no matter how different they are from each other in their historical process, their social development and the movement of their culture, are in such a consideration only members, in a certain sense, only auxiliary factors of the closed, passing through all history in the logical structure of the stages of revealing the cosmos of civilization, today common to all humanity.”

Evolutionary sociology has always tended to identify the meaning of history with either civilization or social progress, thereby ignoring the cultural side itself. historical life. In reality, culture is the “internal mental and spiritual structure of the historical body,” expressing in a specific way the “vital substance” of the latter. Culture is the “soul” of the historical body, shaping and spiritualizing the “matter” of civilizational and social processes occurring in it. The “mental-spiritual” is autonomous relative to the “objective” spheres of life of the historical body. It is capable of evaluating the latter, accepting or rejecting them, approaching them or distancing itself from them.

The result of the cultural design of existence always, even in the case of intensive dialogue with tradition, is something new. The cultural process is as irreversible and unique as civilization and the history of social organization are irreversible and unique. And at the same time, the phases of the cultural movement are not, like the phases of the civilization process, in relation to mutual succession and continuity. “All emanations of culture are always “creations”. They bear the sign of each creation, have the character of “exclusivity” and “one-time use,” in contrast to everything revealed by the process of civilization, which always has the character of “discoveries” and thereby universal significance and necessity, the identification of something already existing.” Everything cultural is spontaneous and unpredictable. You can trace the development trends of the civilization process. It is possible to foresee something about the future forms of social structure. However, it is impossible to scientifically predict either this cultural productivity itself or specific types of cultural design of existence.

Since there is no clear and rigid connection between the spheres of social process, civilization and culture, and in each historical body the combination of these factors is, in principle, unique, the task of the sociology of culture is not to foresee (predict) the dynamics of the cultural process (which, in essence, does not seem possible ), but in understanding the “internal structure” of empirically observed phenomena of history.

“The task of sociological research,” writes Weber, “is to identify the types of the thus broken or closed sense of life and their desire to express themselves in various forms and conditions, to establish their connection with the materially or spiritually created new synthesis of life elements and to explain, on this basis, not only long periods of cultural productivity, its repetition and its essence and the position of great people in it, but also the coming to the fore of various aspects of the expression of culture, the sequence and change of its formal principles, explain or, to express it more carefully and modestly, interpret all this " .

Thus, the task of the sociology of culture is formulated in the form of considering the three layers of the general historical process “in their own dynamics and in the context of a particular historical situation, as well as in determining the nature of their relationships with each other.” Therefore, each of the traditional approaches to social cognition - both causal and immanent - is considered not to be universal, all-encompassing, but instrumental, that is, to have its own boundaries. The causal approach, presented in the evolutionary philosophy of history and sociology, demonstrates its fruitfulness in the study of the processes of socialization and civilization of mankind, while the immanent approach - in research in the field of cultural history (art, literature, music, religion, philosophy). If “intellectual” concepts and ideas can be used for objects of the process of civilization with its universal significance and necessity, then cultural objects in their exclusivity and uniqueness should be approached “only with the help of the “historical” formation of concepts, with concepts and ideas of a “unique essence.”

External story structure

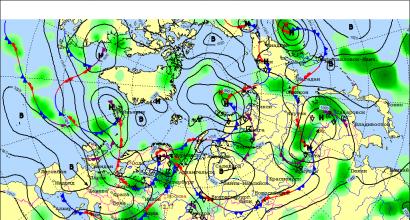

V.'s teaching on the external structure of history is based on the historically changing relationship “man - Earth”. It is this relationship that creates a specific interpenetration of the external and internal image of history and gives it a “great, self-contained periodization.” V. believes that by the middle of the 20th century, the internal structure of history came into such a striking contradiction with its external structure and therefore we “must say goodbye to previous history.”

The first historical period is divided into two sub-periods, which have different “mental-spiritual positions.” The first of these - the so-called chthonic subperiod - dates back to approximately 4000-1200 BC. e., the second lasted from 1200 BC. e. until 1500-1600

In the first subperiod, the spiritual position of the peoples engaged in agriculture “breaks through” the layer of pastoralists to such an extent that it magically fixes the social structure and the general existence of historical formations to a large extent. In the second subperiod, the invading nomads, mentally retaining their chthonic views in whole or in part, in all large historical bodies begin to consider the question of the meaning of existence. As a result, transcendental universal religions, philosophies or attitudes to life that still exist today arise everywhere. These are Taoism and Confucianism in China, Brahmanism and Buddhism in India, Zoroastrianism in Asia Minor, prophetic Judaism in Israel and the tragic and philosophical interpretation of existence in Ancient Greece. During this phase, Western and Eastern Christianity and Islam spread west of the Hindu Kush. If in the first subperiod the magical comprehension of existence predominates, then in the second the mythological and intellectual comprehension of existence already coexist with each other.

In the second subperiod, as a result of the raids of nomadic peoples, state formations in the East and West began to develop fundamentally in various ways. In the East, in India and China, they were transformed into “genuine large organizations”, which, although sometimes striving for expansion, generally remained at rest in themselves. At the same time, to the west of the Hindu Kush, with the arrival of nomadic tribes, “history” arises in the modern sense of the word, understood as “the separation of states, empires and spheres of culture, which in an alien existence replaced each other through seizures, subjugation and destruction.” For three thousand years, from 1200 BC. e. Until about the beginning of the 19th century, being in constant competition and at the same time engaged in exchange and exerting fruitful influence on each other, the states of the Western world sought to establish all-encompassing empires.

Until the end of the first era, it remained characterized by adaptation to nature, which was left as it was, dominating it only with the help of hand tools and the domestication of animals. All this time, the development of technical means of civilization has been characterized by a state of stagnation. The first period of history ends around 1500-1600, during the era of the Reformation.

In the second period of history (1500-1600 - early 1900s) in the depths of Western European civilization There is a radical change in the relationship between man and the Earth, when instead of adapting to the Earth and the world or leaving the world, the tendency to dominate them is established. This period is also divided into two subperiods: “the time of exploration, unification of the Earth” and “the time of saturation,” when “all conditions begin to counteract the continuation of the discovery trends carried out until then.”

The “time of development” includes the emergence of modern empirical science, the development of which already by 1760 leads to a rapid revolution in technology. In socio-structural and political terms, we are talking about the development of modern capitalism, which is supported by the “rationalized, modern, free from all fetters, fully empowered state” that emerged after 1500.

As a consequence of the change in orientation from the otherworldly to this worldly interpretation of existence at the end of the 18th century. Following the transcendental religions of the past, three social religions arise. Their source is Rousseau's idea of the natural existence of man, which, “based on the freedom and equality of people, requires self-determination for all.” Social religions are gradually replacing transcendental religions and taking their place.

The following are distinguished as social religions: 1) democratic capitalism, 2) democratic socialism and 3) Soviet communism. The first of them, which has become predominantly widespread in the United States, is the religion of “freedom and equality of opportunity.” Its peculiarity lies in the recognition of actual inequality between people in modern capitalism as acceptable. In Europe, a predominantly different type of social religion is represented - “the religion of free democratic socialism of one shade or another.” She also views freedom as the highest good, but in order to achieve the necessary balance between freedom and equality of individuals, she considers the transformation of capitalism inevitable. Finally, the third type of social religion “puts above all else equality, understood as social egalitarianism, and for this purpose gives freedom to the power of totalitarianism, which carries out this imaginary social egalitarianism through the means of terror.”

Plunging into the depths of the transcendental layer of reality, a person “never feels like a lonely, isolated subject.” He is both free and part of a wholeness that connects him with other people. No democratic procedures can replace a person’s experience of activating comprehension of the directly transcendental and through it the assimilation of the concepts of freedom and humanity in their absolute meaning. Turning his gaze to intellectuals, Weber believes that it is they who should contribute to the beginning of a return to the comprehension of humanity, the restoration in memory of “an activating comprehension of transcendence, which as such is mostly not felt, although it always surrounds us; it is the true comprehension of transcendence and, with the right vision and understanding, opens the way to the liberating force of initiative of combining present negativism with a positive vision.” A new comprehension of reality, based on the directly transcendent, should open up modern man who has lost traditional faith in transcendental values -PDF

Historical reference

Alfred Weber(1868–1958) was the younger brother of the outstanding German sociologist Max Weber, author of the book “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism,” published in 1905. A. Weber studied art history and archaeology, law and national economics. Having defended his doctoral dissertation in 1895, he began his academic career.

From 1904 to 1907 he taught at Charles University in Prague, his classes were attended by the future writer Franz Kafka. It was here that A. Weber was actively working on a theory that would be published in 1909 under the title “On the Location of Industry.” In 1907, Weber returned to Germany and, under the influence of his brother, became interested in sociology. He never returns to economics. In 1933, as a sign of protest against the Nazis coming to power, A. Weber removed the Nazi flag from the building of the Institute of Social and Government Sciences at the University of Heidelberg, which he headed. The institute would take his name in 1948, at which time Weber resigned and remained unemployed until the end of World War II. Moreover, since 1940 he has been actively involved in the movement of intellectual resistance to Nazism. After the war and until his death, Weber worked at his institute in the field of sociology, history and culture.

Three Points Problem

At the beginning of his theory of industrial location, Alfred Weber reduces the entire set of factors influencing the location of production to three: 1) transport costs, 2) labor costs and 3) agglomeration/deglomeration forces. Next, he consistently studies their separate and joint influence on the geography of industry and its dynamics. This is an important step from Launhardt, who focused only on the first factor.

Weber models transport orientation by solving together with a mathematician George Peake"three points" problem. Apparently, both of them were not familiar with Launhardt’s work, since they nowhere refer to his solutions to a similar problem. Like Launhardt, Weber gives three solutions: mechanical and two geometric. We have already discussed the mechanical ones earlier, but here we will analyze the geometric solutions.

Let there be two point sources of materials and one point sales market. These three points define the so-called standard figure(Fig. 2.5). The production technology is determined by the weight of each material required to produce a given weight of the final product. For example, to produce 1 ton of product it is necessary to spend 1/2 ton of material 1 and 3/2 ton of material 2. Provided that the cost of transporting 1 ton is fixed and equal for any cargo, we will find a point to find production (“standort”), at in which the total transport costs will be minimal.

If we recall Launhardt’s mechanical solution to the problem, its essence boils down to the fact that minimizing transport costs will correspond to minimizing the total potential energy of a triangular system of loads with masses equal to those being moved. If the loads are released, then the system, according to the laws of physics, itself will come to a state of minimum potential energy. If one of the weights does not pull the remaining two all the way, the point of connection of the threads leading to each of the weights is in equilibrium, i.e. standart will be inside the triangle.

Let us now note that the gravitational forces for each load in a state of equilibrium balance each other, i.e. in terms of Fig. 2.5 each vector A is the resultant for the two remaining vectors. This remark allows us to construct a “weight triangle” (on the right in Fig. 2.5). The angles of the weight triangle (indicated by the letters b) are complementary to the angles formed by the point R(standard) and the vertices of the standard figure (indicated by the letters IN).

Rice. 2.5.

Further, from geometry it is known that the size of an angle inscribed in a circle and resting on a given chord does not change for any position of its vertex on the embracing arc of the circle. That is, if you move the point R in Fig. 2.6 along the circle, the value of angle B3 will not change.

Rice. 2.6. Left: a circle with an inscribed edge of the stand figure and the point where the plant is located - the stand. Right: finding a point R at the intersection of three circles

This means that you need to construct such a circle for each edge of the standart figure, and find a point at the intersection of these circles R. Constructing a circle is possible in two ways. First way: the center of the circle is found by building at the ends of the segment A 1 and A 2 corners IN 3 equal to 90° (Fig. 2.6). Indeed, the angle A 1SA 2 is equal to 180-2×(B3-90)=360-2B3, therefore, arc A 1N.A. 2 = 2B3 a inscribed angle A 1RA 2 equals half an arc A 1N.A. 2, i.e. β3. Second way: on the edge A 1A 2, you can construct a triangle similar to a weight triangle so that the angle Α 1ΝΑ 2 was equal to b3, and the remaining two angles were respectively b x and b 2. This will allow you to build a circle around this triangle, on the arc of which there will still be a point R according to fig. 2.6. The intersection of three such circles will again give us the desired standard - a point R.

Weber crystallizes the intuition of a decision in a “material index.” He divides all materials into localized ones, i.e. available only in certain places on the map, and ubiquitous. It is localized materials that need to be transported. Therefore, the stand depends on the ratio of the weight of localized materials used in production to the weight of the final product, i.e. from the "material index". The higher the index, the more production gravitates towards the places of shipment of materials; the lower, the more towards the point of sale. In particular, if the index does not exceed one, then the standorg will be located directly at the point of consumption.

Weber goes on to make another useful point. He divides all raw materials and materials for production into “pure” (they completely transfer their weight to the final product) and “coarse” (part of the weight of the material is lost during the production process). Various components can be considered “clean”, for example, studs for fastening car parts. “Coarse” includes various raw materials, for example, in the production of wheat flour, losses with bran and dust amount to 18% of the mass of refined grain.

“Pure” materials cannot attract production to their location because, from the point of view of transport costs, it makes no difference whether the materials are transported separately or as part of the final product. "Rough" materials can attract a standard if their share in the final product is high enough for the material index to exceed one.

Thus, it turns out that it is quite rational to assemble cars in the area of the sales market, if it is large enough to consume the output of a separate plant. The weight of the finished machine will differ from the total weight of the components only by the weight of their additional packaging, and the use of at least a small amount of local materials makes the material index less than one.

Question: why then are flour mills usually located closer to the point of consumption, although the material index of flour is higher than one, and bran, the main production waste, is used in agriculture, and not in the city? The answer may have to do with two other location factors: labor costs and agglomeration.

Relationship between industrial location and labor costs. Obviously, regions with cheaper labor with comparable “quality” (work culture, productivity, propensity for innovation) will attract industry and force it to deviate from the standard that is optimal in terms of transport costs. To show how this will happen, A. Weber introduces the concept of isodapane. In Fig. 2.7 you can see curves connecting the points at which the costs of deviation from the transport stand (point R) are equal. These are isodapanes. The further the isodapane is from the point R, the higher the deviation costs that correspond to it.

Rice. 2.7.

Points L 1 and L 2 are labor concentration points. If labor savings at a point L 2 compared to point R there will be more deviation costs A 2, then the location of production at the point L 2 will increase profits.

Weber further notes that goods with low transport weights will have larger distances between isodapanes, which increases the likelihood of deviation from the transport stand. He gives examples from his time: for corset production, a 10% reduction in labor costs saves 150 marks per t-km of transported materials in a transport stand, for ceramics - 5.5 marks, for the production of raw sugar - 0.13 marks . With a transportation cost of 5 pfenings per ton-km, we find that these savings allow for a deviation of 3000 km for the first production, 100 km for the second, and 2.6 km for the third.

An increase in average population density, according to Weber, should lead to a reduction in distances between work centers, as well as an increase in the “cultural level” of workers in these centers and, consequently, to an increasing concentration of industry in them. Reducing transport costs will also expand isodapanes and stimulate the work orientation of the industry. However, the opposite force is also at work - increased productivity reduces the share of labor costs in total costs and the attractiveness of work centers. Therefore, capital-intensive industries with a high level of automation can choose a location with little or no consideration for personnel costs.

Agglomeration. Weber considers agglomeration, i.e. the accumulation of industry in one place is the third most important factor of location. Agglomeration allows economies of scale and specialization. Here is how Weber himself describes the deepening specialization in the agglomeration: “The improvement of the technical apparatus leads to the fact that individual, specialized parts of this apparatus begin to be applied to such small and fractional parts of the work process that even in the largest production “partial” machines can no longer be used to the fullest. Hence the need arises to isolate the relevant parts of the production process as auxiliary productions, serving not one, but several main productions. The establishments that appear in this case with such auxiliary productions may not be located next to the main production, but practically the most advantageous is the connection "both in one place, close to each other. The same can be said regarding the renewal and repair of technical equipment." However, the accumulation of industry leads to an increase in land rent, price levels (due to population growth), wages and prices of materials, not to mention the environmental load. If, nevertheless, in the end, location in an agglomeration gives the enterprise a reduction in total costs, factories will be attracted to such points and to each other.

In Fig. 2.8 we can see a situation in which the convergence of three industries somewhere in the shaded area will bring to each a benefit sufficient to cover the losses due to deviation from the transport stand. Weber further proposes to consider the process of agglomeration as the joining or emergence of small industries around a large one. By specifying the function of savings from agglomeration of the mass of produced products in one place and transport costs, Weber derives the radius of attraction of small-scale industries for large-scale production with a given mass of products. Having the geographic density of product output in the country, it is possible to calculate how much mass one agglomeration will attract and how many such agglomerations will produce the entire output.

Does the benefit of agglomeration depend on the mass of materials transported or the share of labor costs? Weber notes that the work orientation of industry leads to agglomeration in one place, which means that industries prone to work orientation will agglomerate most actively. However, transport-oriented industries can also agglomerate, since they will initially be located close to each other.

Rice. 2.8.

Weber concludes his book by considering cases involving dependent proceedings. For example, one production can consume the products of another. Solving the three-point problem step by step for each production separately, Weber shows how the joint transport optimal location of two or more connected plants is determined. As a result, even small changes in the parameters of objects can lead to significant changes in the entire economic geography of the region. This suggests the need to understand and model the connections between industries and even individual enterprises in the region both to assess the consequences of changes in economic policy and to minimize the costs of enterprises moving to new locations due to changed economic conditions (relocation implies both physical movement and and the closure of old enterprises in parallel with the opening of new ones in other places).

Alfred Weber's work is distinguished by its simplicity and logical order. Perhaps that's why it was him for a long time was credited with the formulation and solution of the “three points” problem. One cannot fail to note the insightful analysis of agglomeration for that time, which, of course, contributed to the emergence of a new economic geography - the modern direction of spatial economics, which is discussed further in Chapter. 6. The weak point of Weber's theory was the assumption that all demand is concentrated at one point. Another German economist tried to eliminate this main drawback of his theory 20 years later - August Lesh(see subparagraph 2.2.2).

Another shortcoming of Weber's theory is the lack of competition. In his model, companies do not compete with each other for resources or markets. Moreover, being nearby, they can reduce each other's costs. However, it turns out that enterprises can also gather in clusters because this allows them to sustainably divide nearby markets. This was demonstrated by the American economist Harold Hotelling, having solved the problem of placing two companies in competition for a common sales market.

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber (German: Maximilian Carl Emil Weber, April 21, 1864, Erfurt, Prussia - June 14, 1920, Munich, Germany), known as Max Weber (German: Max Weber) was a German sociologist, philosopher, historian, and political economist.

Weber's ideas had a significant influence on the development of social sciences, especially sociology. Along with Emile Durkheim and Karl Marx, Weber is considered one of the founders of sociological science.

Weber introduced the term “social action” into scientific use. The scientist was a consistent supporter of antipositivist methods, arguing that not a purely empirical, but an “explanatory”, “interpretive” method is better suited for the study of social actions. Within the framework of the concept of understanding sociology based on it, the scientist tried not only to consider this or that social action, but also to recognize the purpose and meaning of what was happening from the point of view of the individuals involved.

The core of Weber's scientific interests was the study of the processes of transition of society from traditional to modern: rationalization, secularization, “disenchantment of the world.” One of the scientist’s most famous works was his dissertation on the Protestant origins of capitalism. Research at the intersection of economic sociology and the sociology of religion was developed in the famous book “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism,” which was published in 1905.

Opposing the Marxist concept of historical materialism, Weber noted the importance of the cultural influences exerted by religion - it was in this that he saw the key to understanding the genesis of the capitalist form of economic management. Subsequently, the scientist studied the religions of China, India and ancient Judaism, trying to find in them the causes of those processes that determined the differences between the economic structure of the West and the East.

In his other famous work, Politics as a Vocation and Profession (1919), Weber defined the state as an institution that has a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence. The sociologist was the first to identify different types of public power, emphasizing that the institutions of the modern state are increasingly based on the rational-legal type. The scientist made a certain contribution to the development of economic history, theory and methodology of economics. Weber's research in the field of rationalization of society influenced the formation of critical theory, which developed mainly within the framework of the Frankfurt School.

Weber became one of the founders of the liberal German Democratic Party, which was formed after the First World War. Later, the scientist unsuccessfully ran for a seat in the German parliament and advised a commission to draft a new constitution. Weber died in 1920 at the age of 56, caused by the Spanish flu pandemic and subsequent pneumonia. Weber's younger brother Alfred also became a researcher in the field of sociology.

Books (12)

Agrarian history of the Ancient World

The next book in the large series “TsFS Publications” (small series “LOGICA SOCIALIS”) is the first book in a two-volume series, which includes three works on historical sociology that are very important for understanding the work of M. Weber: “Agrarian History Ancient world", "Economy History" and "City".

The first book includes “Agrarian History of the Ancient World” and, as an appendix, M. Rostovtsev’s article “Colonate”, which is very important for understanding all three works of M. Weber.

Power and politics

The centuries-old debate about the nature of power between such classics of political thought as Machiavelli and Montesquieu, Hobbes and Schmitt does not lose its relevance today. One of the leading specialists in the field will help you understand the subtleties and nuances of this conversation. political philosophy Alexander Filippov.

Max Weber is one of the greatest political thinkers of the 20th century. He actively participated in the political life of Germany, was a prominent publicist and the author of a number of in-depth studies of modern politics. Weber became famous primarily for his fundamental works, in which, in particular, he proposed a taxonomy of sociological concepts, among which one of the central places is occupied by the concepts of power and domination. In works collected in this volume, combines theoretical and methodological work with concepts, a current analysis of party political life and a broad historical-critical presentation of the evolution of the political profession in the West in the modern era, the era of rational bureaucracy and the charisma of leaders.

This volume, compiled by Alexander Filippov, includes the works “Parliament and Government in the New Germany”, “Politics as a Vocation and Profession” and “Basic Sociological Concepts”.

Introductory article by A.F. Filippova. Comments by Dmitriev T.A.

City

Definitions of “city” can be very different in nature.

What they all have in common is only one thing: that the city is a closed (at least relatively) settlement, a “settled area,” and not one or more separately located dwellings. In cities (though not only in cities), houses are crowded - and today, as a rule, wall to wall - adjacent to each other.

Favorites. Image of society

The book is a collection of works by one of the leading Western sociologists, M. Weber.

The publication includes the following works: “Sociology of Religion”, “Introduction” to “Economic Ethics of World Religions”, “City”, “Social Causes of the Fall” ancient culture", "Rational and sociological foundations of music."

Selected works

The book is a collection of works on sociology by one of the leading Western sociologists of the 19th - 20th centuries. Max Weber (1864-1920), who had and continues to have a significant influence on its development.

The works included in the collection reflect his ideas about the connection between sociology and history, about “understanding sociology”, the concept of “ideal types”, etc. M. Weber is often called in the West “the great bourgeois antipode of Karl Marx” and even “the Marx of the bourgeoisie” "

The book includes: “Protestant ethics and the spirit of capitalism”, research on the methodology of science, various sociological articles.

Science as a calling and profession

This work is a report (translated with slight abbreviations) given by Weber in the winter of 1918 at the University of Munich with the immediate purpose of showing students what their calling was as future scientists and teachers.

About Russia

The collection includes abridged versions of two large essays, full texts or fragments of Max Weber's newspaper articles directly related to Russia. Weber analyzes in them the socio-political situation in Russia in 1905-1906 and 1917-1918. Weber discusses the prospects for liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy in Russia, assesses the various social forces in Russian society and the nature of the Russian revolutionary movement.

The book is intended for everyone who is interested political history Russia.

Political works 1895–1919

The book is a collection of works by an outstanding German sociologist.

Max Weber's articles and speeches on political problems, despite their relevance, had never been published in Russia before and were known to a narrow circle of specialists. This collection is intended to fill this gap.

“Our generation is not destined to see whether the struggle we are waging will bear fruit; whether posterity recognizes us as their ancestors. If we cannot escape the curse that we face—being born after a politically great era—then we must be able to become something else: the forerunners of an even greater one. Will this be our place in history? I don’t know and I’ll just say: the right of young people is to defend themselves and their ideals. And it is not years that turn a person into an old man: he is young as long as he is able to perceive the world with those great passions that nature has invested in us.”

Protestant ethics and the spirit of capitalism

The book contains the work “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism” by M. Weber, where he shows the relationship between Protestant religious values and the development of the “spirit of capitalism,” arguing that in countries where these values dominated, capitalist relations were established faster and easier. The book also includes articles by V.L. Kerov "The modern sound of the theory of M. Weber and A.I. Neusykhin about Protestantism", M.I. Lapitsky " Religious background economic activity", I.V. Zabaeva "Religion and the problem of modernization (on the example of M. Weber and S. Bulgakov)".

WEBER Alfred

WEBER Alfred

Alfred WEBER (July 30, 1868, Erfurt - May 2, 1958, Heidelberg) - German sociologist and economist. He taught at the Universities of Berlin and Prague (1899-1907). From 1907 until the end of his life, he was a professor at the Department of Economics and Sociology at the University of Heidelberg. During the Nazi period, his teaching was interrupted; continued to work at the university only after the end of World War II.

Weber builds a socio-philosophical concept on the opposition of civilization and culture, borrowed from O. Spengler. However, Weber sees civilization, culture and society not as successive processes in history, but as different processes. The process of civilization as a rational goal-setting is primarily represented in the developing set of technical means with the help of which each individual ensures his survival and achieves dominance over nature (science, technology, social institutions - the state, created for the rational organization of society and contributing to its preservation and safety its members).

The movement of culture is fundamentally different from the process of civilization. He views culture as characterized by flourishing and aging, parallelism in fate, repeated in cultural creativity and in the change of artistic styles. Culture is confined to the historical body in which it arises. It represents the spiritual conditioning of a number of symbols. The cultural is objectified in work of art and in ideas. The creativity of culture is tragic in its essence, since the existence of culture has its own laws and is destructive in relation to man. The goals of the development of civilization and culture are opposite. The process of civilization is associated with the rationalization of all life and consciousness. Culture does not progress, but reflects the beginning in the soul, being a meaning-forming function of historical bodies. The movement of culture creates different worlds that arise and die along with historical bodies, unique and unique in contrast to civilization. Weber talks about the correlation between culture, civilization and social movement. Therefore, he rejects the methods of natural and social sciences characteristic of neo-Kantianism.

In “The Third or Fourth Man” (Der Dritte oder der Vierte Mensch: Vom Siun des geschichlichen Daseins, 1953), Weber analyzes the supravital (transcendental) realms of meaning that affect man. He conceives of transcendence as the sphere of action of invisible spiritual forces that permeate all living things and become immanent in human life. He refers to spiritual-mental transcendence as values, the individual mental-spiritual core of the personality, and human freedom. Focusing on the formation of a new anthropological type (“fourth man”), in contrast to the “third man” functionary Western civilization, Weber gives the crisis of European culture, its anthropological foundations.

Works: Favorites: The Crisis of European Culture. St. Petersburg, 1999; Lieber den Standort der Industrien. Bd. l Reine Theorie des Standorts. Tub., 1909; Religion und Culture. Münch., 1912; De Krise des modernen Staatsgedanken in Europa. Hdeb., 1925; Kulturgeschichte als Kultursoziologie. Leiden, 1935; Prinzipien der Geschichts- und Kultursoziologie. Hdib., 1951.

Lit.: Ecken R. Kultur, Zivilisation und Gesellschaft: Die Geschichtstheorie A. Webers. Tub., 1990; Kruse V. Soziologie und “Gegenwartskrise”. Wiesbaden. 1990.

G. B. Gutner, A. P. Ogurtsov

New Philosophical Encyclopedia: In 4 vols. M.: Thought. Edited by V. S. Stepin. 2001 .

See what "WEBER Alfred" is in other dictionaries:

Alfred Weber (1868 1958) German. cultural sociologist and economist. Prof. Prague (1904 07) and Heidelberg. (since 1907) un comrade After the National Socialists came to power, they removed the Rev. activities and devoted himself entirely to writing scientific... ... Encyclopedia of Cultural Studies

- (Weber) (1868 1958) German economist and sociologist. Brother of M. Weber. He developed the concept of the sociology of history and culture, according to which the course of history is determined by the process of spiritual creativity carried out by the intellectual elite. Political Science... Political science. Dictionary.

- (Weber) (1868 1958), German economist and sociologist. Brother of M. Weber. He developed the concept of the sociology of history and culture, according to which the course of history is determined by the process of spiritual creativity carried out by the intellectual elite. Was engaged... ... encyclopedic Dictionary

Alfred Weber (July 30, 1868, Erfurt, ‒ May 2, 1958, Heidelberg), German bourgeois economist and sociologist. Brother of M. Weber. Professor of economics and sociology at Prague (1904‒07) and Heidelberg (1907‒58, with interruptions during the years of fascism)… … Great Soviet Encyclopedia

This article may contain original research. Add links to sources, otherwise it may be set for deletion. More information may be on the talk page. (May 25, 2011) ... Wikipedia

Alfred Weber Alfred Weber Portrait at the University of Heidelberg Date of birth: July 30, 1868 Place of birth: Erfurt Date of death: May 2 ... Wikipedia

- (18681958), German economist and sociologist. Brother of M. Weber. He developed the concept of the sociology of history and culture, according to which the course of history is determined by the process of spiritual creativity carried out by the intellectual elite. Dealing with problems... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

Contents 1 Known media 1.1 A 1.2 B 1.3 C ... Wikipedia

- (Weber) (1864 1920), German sociologist, historian, economist and lawyer. Brother of A. Weber. Weber's methodology, based on neo-Kantian epistemology, is based on the distinction between experimental knowledge and values; the concept of “understanding”, according to which social... ... encyclopedic Dictionary

1. Alfred Weber (07/30/1868, Erfurt 05/2/1958, Heidelberg) German social philosopher, sociologist and economist. Professor at Prague (1904 1907) and Heidelberg (since 1907) universities. Scientific activity started as an economist, then... ... Encyclopedia of Sociology

Books

- Classics of sociology. Classic works on the theory of society (CD), Kostyuk K. N.. Electronic publication "CLASSICS OF SOCIOLOGY: CLASSIC WORKS ON THE THEORY OF SOCIETY" was prepared by the author-compiler - candidate of pedagogical sciences K. N. Kostyuk in accordance with ...

WEBER Alfred (30.7.1868, Erfurt - 2.5.1958, Heidelberg), German economist and sociologist. Brother of M. Weber. He was educated in Bonn (1888, art history and archaeology), Tübingen (1889, law) and Berlin (1890-92, law and national economy). In 1895 he defended his doctoral dissertation at the University of Berlin under G. von Schmoller. Professor of economics and sociology at Prague (1904-1907) and Heidelberg (1907-58, with breaks in 1914-18 and 1933-45) universities. In March 1933, as a sign of protest against the Nazi victory in the elections, he removed the fascist flag from the building of the Institute of Social and Government Sciences at Heidelberg University, which he headed, and voluntarily resigned. Until 1945, he was in “internal emigration”, providing intellectual resistance to the Nazi regime.

In 1909, he created the theory of industrial location, according to which an industrial enterprise strives to occupy the most advantageous location in relation to sources of raw materials and the labor market, ensuring the lowest costs for entrepreneurs.

Under the influence of M. Weber and the philosophy of life, especially the ideas of O. Spengler, Weber turned to the problems of the sociology of history and culture and proposed his original concepts. History, understood by Weber as an ever-changing, mobile and, in particular, unstable equilibrium, has an internal and external structure. Internal structure is a characteristic of any “historical body”, consisting of three independent components: social process (economics, social relations, politics and state), the process of civilization (science and technology) and the movement of culture (religion, philosophy, art). The task of the sociologist is to reveal the unique combination (constellation) of these factors in each specific historical body, which has its own spatio-temporal unity. The external structure of history describes the coexistence and interaction of various historical bodies in the context of human-Earth interaction. From the 4th millennium BC until the 16th century, the various historical formations generally remained quiescent within themselves. During the era of the Reformation, in the depths of Western European society, a tendency arose for the active development of the Earth and its subordination to human needs. Thus, for the first time in human history, the civilizational component began to prevail over the cultural one. By the beginning of the 20th century, having achieved complete economic dominance over the Earth it united, the capitalist West was faced with an obstacle to unlimited scientific and technological development in the form of the limitations of the planet itself. Two world wars of the 20th century showed that the discrepancy between the process of civilization and the movement of culture turned out to be destructive for the historical body of Western civilization, and humanity was not ready for the new conditions of its existence.

The outcome of the historical process, according to Weber, is not predetermined and depends on the struggle between the tendencies of freedom and unfreedom. The fate of planetary civilization depends on how actively the rationalized mass functionary will be opposed by the heir of ancient humanity, who has restored contact with the world of the immanent-transcendent.

Works: Theory of industrial location. L.; M., 1926; Gesamtausgabe. Marburg, 1997-2003. Bd 1-10; Favorites: The Crisis of European Culture. St. Petersburg, 1998.

Lit.: Luoma M. Die drei Sph ären der Geschichte. Hels., 1959; Eckert R. Kultur, Zivilisation und Gesellschaft: Die Geschichtstheorie A. Weber. Tub., 1970; Pogorely A.I. Criticism of modern bourgeois sociology of culture. K., 1987; Demm E. Ein Liberaler in Kaiserreich und Republik. Boppard am Rhein, 1990; Parton T.A., Cherny Yu. Yu. Man in the flow of history: an introduction to the sociology of culture by A. Weber. M., 2006; Kepeszczuk J. A. Weber, Schriften und Aufs ätze. 1897-1955. Bibliography. Münch., 1956.